1782 Le Roi des

aulnes, poème de Johann Wolfgang Goethe

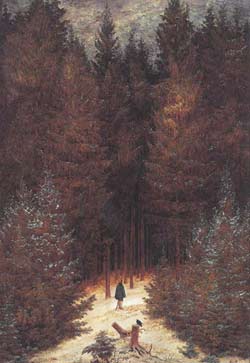

1808-1835 Caspar David Friedrich peint les œuvres

les plus marquantes du mouvement romantique parmi lesquelles Procession

à l’aube, L’Arbre aux corbeaux, Arbre solitaire,

Chêne sous la neige, La Croix dans la Montagne, Le Chêne,

Un homme et une femme contemplant la lune, Le Chasseur dans la forêt,

etc.

1812-1814 Recueil de contes de Jacob et Wilhelm Grimm

(Hänsel et Gretel, Le petit Poucet, Blanche-Neige et les sept nains,

Le Petit Chaperon Rouge)

1868 Légendes de la forêt viennoise, composition

de Johann Strauss fils

1876 Siegfried, opéra de Richard Wagner

1893 Hänsel et Gretel, opéra de Engelbert Humperdinck

1924 Die Nibelungen, film de Fritz Lang

1931 Légendes de la forêt viennoise, récits

de Ödön von Horvath

1950 Chemins qui ne mènent nulle part, essai

philosophique de Martin Heidegger

1950 Schwarzwaldmädel (La fille de la Forêt-Noire)

de Hans Deppe, premier Heimatfilm, genre sentimental folklorique se

déroulant dans la campagne allemande ou autrichienne et prônant

des valeurs conservatrices.

1952 Scènes de la vie d’un faune, roman

de Arno Schmidt

1969 Scènes de chasse en Bavière, film

de Peter Fleischmann

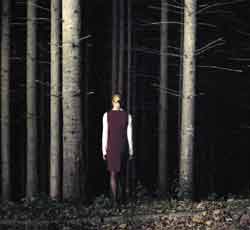

Et cela depuis l’époque où les Germains croyaient qu’un arbre toujours vert, nommé Yggdrasil, renfermait l’univers tout entier jusqu’au concept de « Waldsterben » (littéralement mort de la forêt) qui, au début des années 1980, accapara les média et déclencha des réactions proches de l’hystérie collective à l’annonce du dépérissement progressif du patrimoine arboricole. Mais c’est au XIXème siècle, avec les frères Grimm et leurs Contes, ainsi qu’avec le mouvement romantique, que la forêt devient à proprement parler la matrice de l’imaginaire esthétique germanique et que se compléxifie son système de représentations.